Categories

- Antiques & Collectibles 13

- Architecture 36

- Art 48

- Bibles 22

- Biography & Autobiography 813

- Body, Mind & Spirit 142

- Business & Economics 28

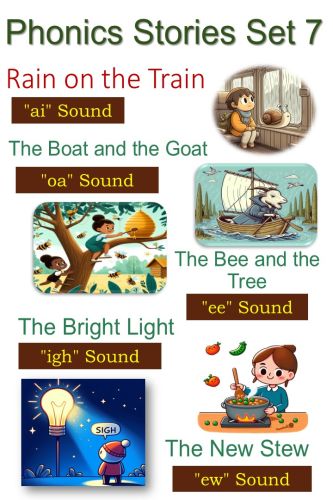

- Children's Books 16

- Children's Fiction 13

- Computers 4

- Cooking 94

- Crafts & Hobbies 4

- Drama 346

- Education 46

- Family & Relationships 57

- Fiction 11829

- Games 19

- Gardening 17

- Health & Fitness 34

- History 1377

- House & Home 1

- Humor 147

- Juvenile Fiction 1873

- Juvenile Nonfiction 202

- Language Arts & Disciplines 88

- Law 16

- Literary Collections 686

- Literary Criticism 179

- Mathematics 13

- Medical 41

- Music 40

- Nature 179

- Non-Classifiable 1768

- Performing Arts 7

- Periodicals 1453

- Philosophy 64

- Photography 2

- Poetry 896

- Political Science 203

- Psychology 42

- Reference 154

- Religion 513

- Science 126

- Self-Help 84

- Social Science 81

- Sports & Recreation 34

- Study Aids 3

- Technology & Engineering 59

- Transportation 23

- Travel 463

- True Crime 29

History of Dogma, Volume 2 (of 7)

by: Neil Buchanan

Description:

Excerpt

HISTORICAL SURVEY.

The second century of the existence of Gentile-Christian communities was characterised by the victorious conflict with Gnosticism and the Marcionite Church, by the gradual development of an ecclesiastical doctrine, and by the decay of the early Christian enthusiasm. The general result was the establishment of a great ecclesiastical association, which, forming at one and the same time a political commonwealth, school and union for worship, was based on the firm foundation of an "apostolic" law of faith, a collection of "apostolic" writings, and finally, an "apostolic" organisation. This institution was the Catholic Church. In opposition to Gnosticism and Marcionitism, the main articles forming the estate and possession of orthodox Christianity were raised to the rank of apostolic regulations and laws, and thereby placed beyond all discussion and assault. At first the innovations introduced by this were not of a material, but of a formal, character. Hence they were not noticed by any of those who had never, or only in a vague fashion, been elevated to the feeling and idea of freedom and independence in religion. How great the innovations actually were, however, may be measured by the fact that they signified a scholastic tutelage of the faith of the individual Christian, and restricted the immediateness of religious feelings and ideas to the narrowest limits. But the conflict with the so-called Montanism showed that there were still a considerable number of Christians who valued that immediateness and freedom; these were, however, defeated. The fixing of the tradition under the title of apostolic necessarily led to the assumption that whoever held the apostolic doctrine was also essentially a Christian in the apostolic sense. This assumption, quite apart from the innovations which were legitimised by tracing them to the Apostles, meant the separation of doctrine and conduct, the preference of the former to the latter, and the transformation of a fellowship of faith, hope, and discipline into a communion "eiusdem sacramenti," that is, into a union which, like the philosophical schools, rested on a doctrinal law, and which was subject to a legal code of divine institution.

The movement which resulted in the Catholic Church owes its right to a place in the history of Christianity to the victory over Gnosticism and to the preservation of an important part of early Christian tradition. If Gnosticism in all its phases was the violent attempt to drag Christianity down to the level of the Greek world, and to rob it of its dearest possession, belief in the Almighty God of creation and redemption, then Catholicism, inasmuch as it secured this belief for the Greeks, preserved the Old Testament, and supplemented it with early Christian writings, thereby saving—as far as documents, at least, were concerned—and proclaiming the authority of an important part of primitive Christianity, must in one respect be acknowledged as a conservative force born from the vigour of Christianity....