Categories

- Antiques & Collectibles 13

- Architecture 36

- Art 48

- Bibles 22

- Biography & Autobiography 813

- Body, Mind & Spirit 142

- Business & Economics 28

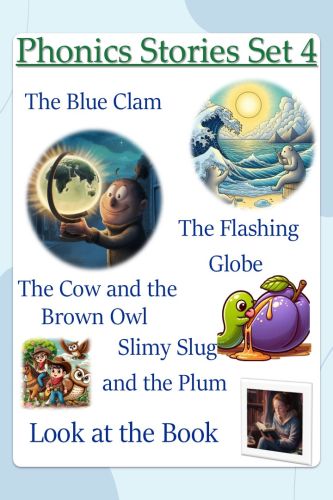

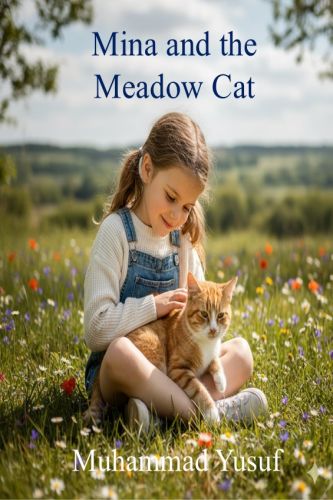

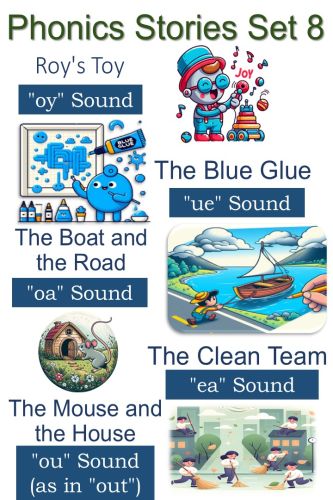

- Children's Books 15

- Children's Fiction 12

- Computers 4

- Cooking 94

- Crafts & Hobbies 4

- Drama 346

- Education 46

- Family & Relationships 57

- Fiction 11828

- Games 19

- Gardening 17

- Health & Fitness 34

- History 1377

- House & Home 1

- Humor 147

- Juvenile Fiction 1873

- Juvenile Nonfiction 202

- Language Arts & Disciplines 88

- Law 16

- Literary Collections 686

- Literary Criticism 179

- Mathematics 13

- Medical 41

- Music 40

- Nature 179

- Non-Classifiable 1768

- Performing Arts 7

- Periodicals 1453

- Philosophy 64

- Photography 2

- Poetry 896

- Political Science 203

- Psychology 42

- Reference 154

- Religion 513

- Science 126

- Self-Help 84

- Social Science 81

- Sports & Recreation 34

- Study Aids 3

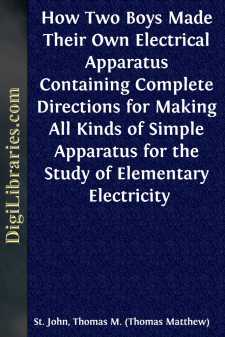

- Technology & Engineering 59

- Transportation 23

- Travel 463

- True Crime 29

The Voice of the Machines An Introduction to the Twentieth Century

Categories:

Description:

Excerpt

THE MEN BEHIND THE MACHINES

I

MACHINES. AS SEEN FROM A MEADOW

It would be difficult to find anything in the encyclopedia that would justify the claim that we are about to make, or anything in the dictionary. Even a poem—which is supposed to prove anything with a little of nothing—could hardly be found to prove it; but in this beginning hour of the twentieth century there are not a few of us—for the time at least allowed to exist upon the earth—who are obliged to say (with Luther), “Though every tile on the roundhouse be a devil, we cannot say otherwise—the locomotive is beautiful.”

As seen when one is looking at it as it is, and is not merely using it.

As seen from a meadow.

We had never thought to fall so low as this, or that the time would come when we would feel moved—all but compelled, in fact—to betray to a cold and discriminating world our poor, pitiful, one-adjective state.

We do not know why a locomotive is beautiful. We are perfectly aware that it ought not to be. We have all but been ashamed of it for being beautiful—and of ourselves. We have attempted all possible words upon it—the most complimentary and worthy ones we know—words with the finer resonance in them, and the air of discrimination the soul loves. We cannot but say that several of these words from time to time have seemed almost satisfactory to our ears. They seem satisfactory also for general use in talking with people, and for introducing locomotives in conversation; but the next time we see a locomotive coming down the track, there is no help for us. We quail before the headlight of it. The thunder of its voice is as the voice of the hurrying people. Our little row of adjectives is vanished. All adjectives are vanished. They are as one.

Unless the word “beautiful” is big enough to make room for a glorious, imperious, world-possessing, world-commanding beauty like this, we are no longer its disciples. It is become a play word. It lags behind truth. Let it be shut in with its rim of hills—the word beautiful—its show of sunsets and its bouquets and its doilies and its songs of birds. We are seekers for a new word. It is the first hour of the twentieth century. If the hill be beautiful, so is the locomotive that conquers a hill. So is the telephone, piercing a thousand sunsets north to south, with the sound of a voice. The night is not more beautiful, hanging its shadow over the city, than the electric spark pushing the night one side, that the city may behold itself; and the hour is at hand—is even now upon us—when not the sun itself shall be more beautiful to men than the telegraph stopping the sun in the midst of its high heaven, and holding it there, while the will of a child to another child ticks round the earth. “Time shall be folded up as a scroll,” saith the voice of Man, my Brother. “The spaces between the hills, to ME,” saith the Voice, “shall be as though they were not.”

The voice of man, my brother, is a new voice.

It is the voice of the machines.

II

In its present importance as a factor in life and a modifier of its conditions, the machine is in every sense a new and unprecedented fact. The machine has no traditions. The only way to take a traditional stand with regard to life or the representation of life to-day, is to leave the machine out. It has always been left out. Leaving it out has made little difference. Only a small portion of the people of the world have had to be left out with it.

Not to see poetry in the machinery of this present age, is not to see poetry in the life of the age. It is not to believe in the age.

The first fact a man encounters in this modern world, after his mother’s face, is the machine. The moment be begins to think outwards, he thinks toward a machine. The bed he lies in was sawed and planed by a machine, or cast in a foundry. The windows he looks out of were built in mills....